Essays

Men. A constant desire, sometimes simmering, often burning. Never sated. And for him, I knew, it had been even longer. We shared in this struggle.

Wig-Wag: “Magnolia”

I wait for my father to die, and I pry the Magnolia disc from its plastic tray case and slip it into the machine for the tenth, the twentieth, the thirtieth time. I can’t make a neat pile of the mess between me and my father. So I watch the strands of this story instead, watch them weave into the most wondrous web. How they build and tremble and collide in a symphony that makes each character’s pain more meaningful than just the random collateral damage of coincidence.

Witch Craft Magazine: “Blank Spaces”

After we buried you, my sisters and I opened the doors of the apartment where you’dlived alone for fourteen years. Your rooms, so unaccustomed to crowds, filled with the ceaseless din of family and friends from all the different stages of our three lives. Snow had fallen at the cemetery. Now all these warm bodies surrounded us to fill the gap of you, if only for an evening.

Catapult: “I Want My Mommy and I’m Glad She’s Not Here For Covid-19”

She smoked until the very end, the night Doug Jones beat Roy Moore in the Alabama Senate race. I can picture her smoking her last cigarette as she retweeted someone calling Roy Moore a motherfucker. We found that last cigarette floating in a cup of water by her bedside, a makeshift ashtray. She didn’t die hooked up to a ventilator, but peacefully in her sleep.

Snowflakes land on the mound of dirt piled atop this shovel, adding to its weight. The dirt is heavy. I forgot my gloves. The wooden handle is cold. My left hand holds the neck, steady, while my right hand—the same fingers that reached into your open casket and touched your stiff, empty belly—rotates the shovel.

(Shortlisted for “The Body” Contest judged by T. Kira Madden)

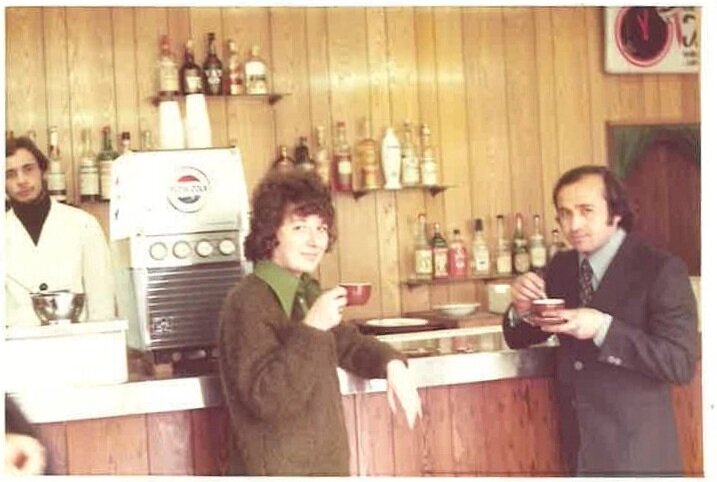

After my mother didn’t wake up; after the snow drifted down to mix with dirt like cream as the gravediggers heaped earth atop her casket; after the drive home to the apartment where she lived alone, now full of mourners; as the weight of the grief coursed through my body and pulled me down, someone asked if I wanted coffee.

Margaret’s husband Michael co-owned the Bowery Ballroom and the Mercury Lounge, two iconic rock clubs on New York’s Lower East Side where I worked for a decade—my homes away from home. Margaret kept the books, but she was more than a bookkeeper. She was the den mother to all of us who worked there. On the cards we printed for her memorial we wrote, “the heart and soul of The Bowery Ballroom.”

Gertrude Press: “Marrow”

When I got off the plane at JFK, my mother wasn’t waiting. She wasn’t answering phone calls or texts, either. Very unlike her. I moved back and forth from the air conditioned terminal to the New York heat wave glare of the curb outside, searching among the glinting windshields of jockeying taxicabs to catch sight of her and her little green car.

The searching faces of those who once had homes, now on the run or corralled into camps, their entire lives carried on their backs, are flattened on our screens. They once lived in homes. They lived in cities and in villages, raised their families in houses, on farms, in apartment buildings teeming with life.

(Appeared in print in Origins Journal, re-published online at The Manifest Station.)

Vol. 1 Brooklyn: “Sister’s Community Hardware”

His name was Abraham. I think. If I’m being honest, I don’t really remember his name, though everything else about him sticks in my memory like a plastic bag stuck in a tree’s branches. We met exactly four times. I hired him to build some shelves in my old Brooklyn apartment.

The trace of my father’s hand on my back. He only ever struck me once, when I fiddled with the radio knob in the car while he talked business on his cell phone. I told him never to hit me again. If only I’d understood the other ways that he was flaying me, and had put a stop to those.